Bricks, Gold, and the Courage of Three Helena Housewives

Following our train ride, my sisters, our aunt, and I took a walk around the village. We found a pavilion among the historic buildings and, following my aunt’s lead, we ran and danced around the restored wood and chorused Frank Sinatra’s “L.O.V.E.”

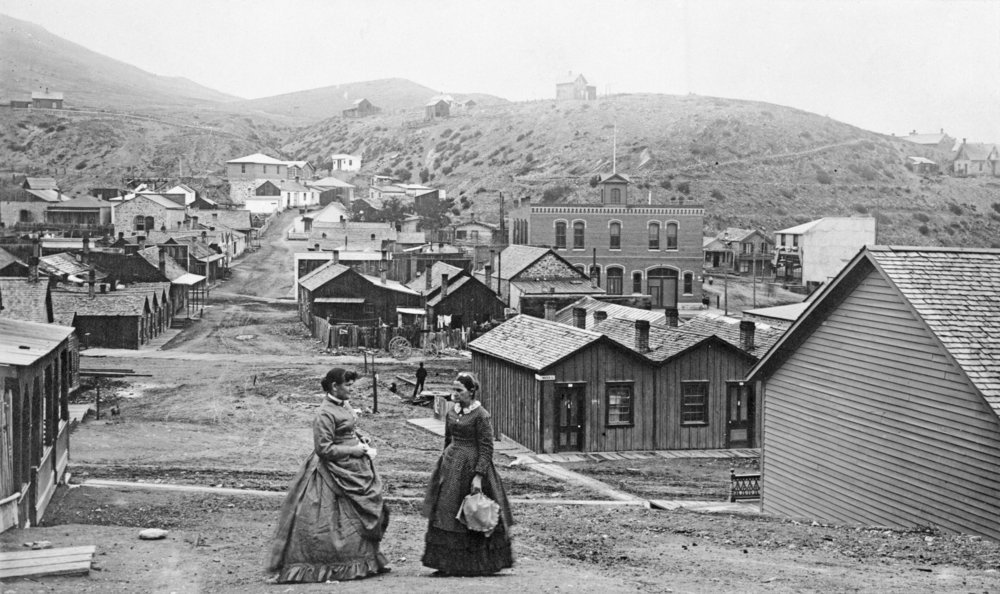

This was Helena’s oldest neighborhood, Reeder’s Alley, which is about 150 years old. Connected to Helena’s downtown area, it’s now home to offices, non-profits, and local businesses. Reeder’s Alley’s buildings trail up Mount Helena’s city park and overlook all of Helena’s succeeded infrastructure—like the past overlooking the present.

In the 1950s, when the same buildings had only been around for 80 years, Helena city planners wanted to demolish the neighborhood. The decision faced little controversy, as the surrounding neighbors of the ‘50s were up for a new change of pace. Yet, a resident of the neighborhood above, Pat Boedecker, thought the area was worth saving. In 1959, she met for lunch with her friend Eileen Harper and in the end, they agreed they would do something about it.

The alley was fashioned by a stone mason and brick layer named Louis Reeder during the height of the Last Chance Gulch Gold Rush. From the start to finish of the boon period, there was 19 million dollars’ worth of gold minedfrom the area.

The miners lived in Reeder’s Alley—where most buildings were built to last. Eventually, time passed and claims dried up, causing miners to move from the area, which left space for other tenants like cooks, laborers, and seasonal workers.

Much like Butte and other mining towns in the West, Helena used to have a thriving red-light district. According to “Silk Stocking’s in Montana’s Mining Towns,” prostitution accounted for the largest source of employment for single women for two decades after 1886.

The red-light district formerly below Reeder’s Alley, was destroyed by massive earthquakes in 1935. All that remained was a characteristic concrete wall trail up a section of the village that was formerly adjacent to the red-light district,built originally to prevent solicitation within the alley.

Near the red-light district was a Chinese settlement. According to Helena’s former interpretive historian Ellen Baumler in an article called, “We are Learning to Do Things Better: A Women’s History of Helena’s First Neighborhood,” the white male workers heavily segregated the services and businesses of the Chinese district, and by the 1930s eventually drove them out. However, for a brief time, the women of the red-light district and the Chinese businesses had a “symbiotic relationship,” according to Baumler. Women relied on Chinese restaurants, physicians, and herbalists for meals, birth control, and other remedies.

Their kinship offers a historical testament to finding who can be helped and who can help in dismal times. The last remnant of the Chinese district is the Yee Wau Cabin formerly owned by brothers who used to distribute merchandise and groceries. The cabin is now a privately owned building endorsed and recognized in Reeder’s Alley tours.

Reeder’s Alley was affected by the earthquakes but remained largely intact. Still, the neighborhood originally built for miners was slowly emptying. The lack of tenants and general activity turned city planners’ attention to its diminishing value. The surrounding neighborhoods, supposing new buildings would bring in better opportunities and poorly associating it with the former Chinese and red-light district, did not push back on this decision to demolish the buildings.

Boedecker and Harper, knowing most people assumed the area would be destroyed, took action to save it. They planned to buy up, clean, and renovate as many of the buildings as they could so that historic Reeder’s Alley could be preserved and create a space for opportunity. Boedecker and Harper enlisted the help of Jane Tobin, the granddaughter of a mercantile company owner. They knew Tobin would be attracted to the idea of preserving the historic site.

Over three years, one building at a time, the housewives collected each asking price.Although they were financially invested in several buildings, their husbands and children had no idea as to what the women were doing. During work and school hours—while also completingall of their housework—they met up daily to renovate the buildings to resell. They cleaned, hauled trash, installed drywall, and knocked down partitions.

Eventually, they drew the attention of neighbors. Some Helena residents were inspired and offered their knowledge, labor, and equipment. Yet others thought crudely of the work they were doing, thinking it was disrespectful for them to have ambitions outside of their family, deciding they were arrogant to think they could pull it off, or simply because they were women. Despite all that disparagers would say, the women stuck to their ambitions and pressed onward.

Boedecker knew that if the city planners had gone through with the demolition, nothing would have changed for the people in the area. Some groups, like women, were stuck in their positions, whether financially or socially, and by taking on the project, she got to have a say in what their community’s future looked like.

Boedecker risked her financial privilege and her social standing in hopes of producing a space for artists to create, build, and share their work through galleries in the neighborhood. Harper joined her because she was critical of the lack of spaces for women to socialize and entertain themselves. Tobin wanted to prove that she could save the area and perserve its inherent historical value.

They all succeeded.

The women acquired more and more property in Reeder’s Alley, even offering other women artists one year’s free rent in exchange for cleaning up their units. Reeder’s Alley became an established artist colony containing antiques, pottery, glass, and book shops, affording women greater opportunities to socialize, enjoy the arts, and go out to lunch.

After buying all the available buildings in Reeder’s Alley, the group designated it the Reeder’s Alley Corporation. After they finished their work in 1962, Harper eventually moved out of state, and Boedecker was inactive by 1964. Tobin and a new member, Grayce Loble, kept the corporation until 1974, when they chose to dissolve ownership.

In 2005, Boedecker wrote a book called Reeder’s Alley: History, Housewives, and Art, about her experiences. She describes how after she left, she operated a restaurant in the very first building the women purchased and following that time she was “compelled by the satisfaction of feeding and nourishing people.”

All these women had the insight and bravery to turn this neighborhood into what it is today: a tourist attraction, the longest-standing territorial neighborhood, and contemporarily, a thriving business and office district for the people of Helena.

The alley represents what ordinary people can do for their communities. It is a place where people can make memories.

Bricks, Gold, and the Courage of Three Helena Housewives

Story by Emily Tollakson

Photos courtesy of Montana Historical Society

A deep and sharp “Woooh-woooh” pierces the air as the tour train honks, causing me to jolt at the noise and its rumble throughout the train car. I was 6 when I took Helena’s Last Chance Tour train for the first time. It is a family-friendly, hour-long tour, and among its installments is a cruise through a restored miner’s village.